Dressing the Ore

Pareusi an Moon

Getting the ore out of the ground was only the first part of the process. Once it had been brought it up the surface, the time-consuming, labour-intensive job of processing it began. But how did they do this by hand? And why did women have such an important role to play?

During the 18th century, most of the ore dressing (or processing) was done by hand. From the early 19th century, it became much more mechanised but female and child labour remained particularly important especially in relation to copper mines.

Miners’ children started work by the age of eight or nine – shovelling and hauling ore, or tending the dressing floors.

Women and girls in mining

Although they didn’t work below ground, women and girls played a big part in the Cornish mining industry. Known as ‘bal maidens’, (the word ‘bal’ is Cornish for ‘mining place’) they dressed the ore brought up from underground. It was hard, physical work which soon took a toll on their health and appearance. While they tried to protect their faces from the sun, wearing cardboard hoods (‘gooks’) to shade their complexions, accounts from the time often mention their rough, chapped hands.

Fancy gloves bought from the chapman weren't a luxury for these women, but a way of trying to stay young and attractive.

Teams of women and girls were also employed in barrowing ore around the dressing floors. They worked in pairs using hand barrows, often carrying over 68kg (more than the weight of an average man) between them.

Copper was by far the most valuable mineral produced in Cornwall and west Devon during the 18th and 19th centuries (the period to which our World Heritage Site inscription applies), giving around five times more profit on average.

Processing copper

Copper ore was dressed somewhat differently than tin and was usually sorted and crushed by hand. Copper dressing relied extensively on manual labour throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, though mechanisation did play a part. Copper crushers (‘Cornish rolls’) were introduced in the early 19th century and low grade or otherwise difficult ores were also stamped at some mines.

1. Copper ore was spalled in the same way as with tin.

2. The younger girls washed and sorted the ore. This was a skilled but wet and dirty job which took knowledge and considerable concentration.

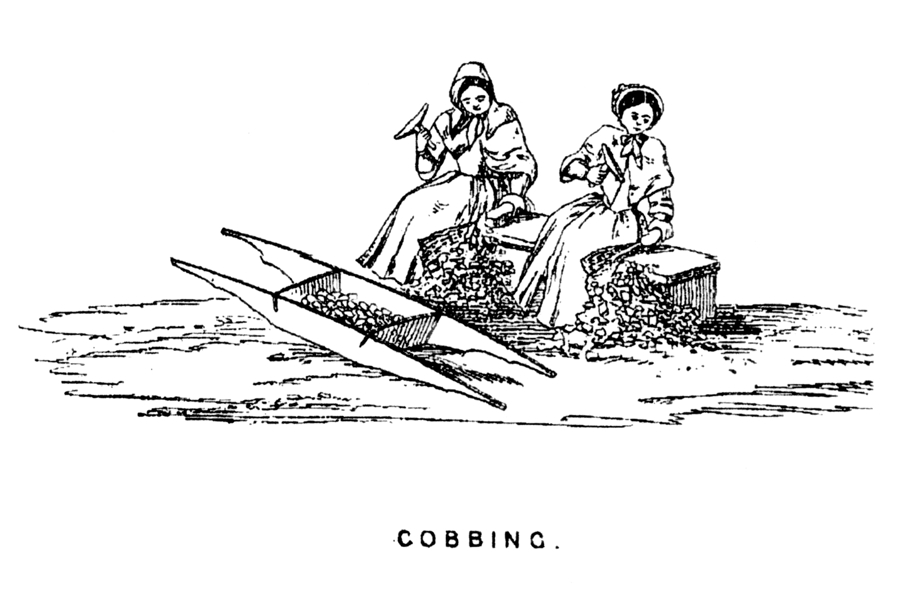

3. ‘Cobbers’ broke the picked ore into pebble-sized pieces using short handled hammers.

4. ‘Buckers’ used flat-faced hammers to grind the cobbed ore into fine powder. Cobbing and bucking were both strenuous jobs that only the strongest women could do.

5. Mechanical ‘jigging’ used water to sift out the heavier particles of ore from the lighter waste (‘gangue’).

Processing tin

Tin ore was initially crushed and concentrated at the mine and underwent a variety of processes which, to a degree, differed from site to site. The product (cassiterite or ‘black tin’) was always smelted in Cornwall up until 1838, due to Stannary requirements, with the last works surviving until the 1930s – ‘Seleggan’ at Carnkie closing in 1931.

1. Once the ore was brought to the surface, it was usually broken up initially by male labourers

2. Spalling was the next part of the process. The ore was broken up into smaller pieces by women and girls using long handled hammers.

3. Stamping - using steam powered machines called stamps to crush the ore with water.

4. When crushed the finest material suspended in water (known as ‘pulp’) was sent to settling strips or buddles, where water flow and gravity separated the heavy tin ore from the lighter waste (‘gangue’) minerals. Children were often employed at this stage.

5. The part-processed ore was sent on to be put through the trunks and kieves.

6. Next, the ore was passed through the tin frames.

7. The final stage of the process was the jigging (sieving) of the heavier particles, which was done by stronger boys or women by hand, or by boys or girls using semi-mechanised jigging boxes.

Processing arsenic

Arsenic was a contaminant of tin ore particularly which had to be removed by heating or ‘calcining’ (it made the tin metal brittle and reduced its value). Purpose-built calciners were used for this with by far the most common model being the Brunton, though the Merton and Oxland types also saw limited use.

Arsenic became a marketable commodity in the latter 19th century with eventual uses in dye and pigment manufacture, as an insecticide, and in medicines. Elaborate stone chambers were subsequently constructed adjoining the calciners to condense the cooling arsenic gasses as arsenic oxide. This was later refined either at the mine or in special refineries built in the arsenic-producing districts.