Women in Mining

Benenes yn Balweyth

Women in Mining

Not only did women play a key part in the home life of miners by keeping their homes and smallholdings running whilst raising families alongside taking in extended family members, they also worked at the mines themselves. Known as Bal maidens - from “bal” meaning “mining place” in our Cornish language - women and girls were found in great numbers at many Cornish mines, skilfully sorting ore and wielding heavy “bucking” and “cobbing” hammers” to break the rock before further processing.

Women were active in methodism - the “miners’ religion” - and have also been recorded as occupying more senior positions in mining. Women played an essential part in the Cornish mining story.

Bal Maidens

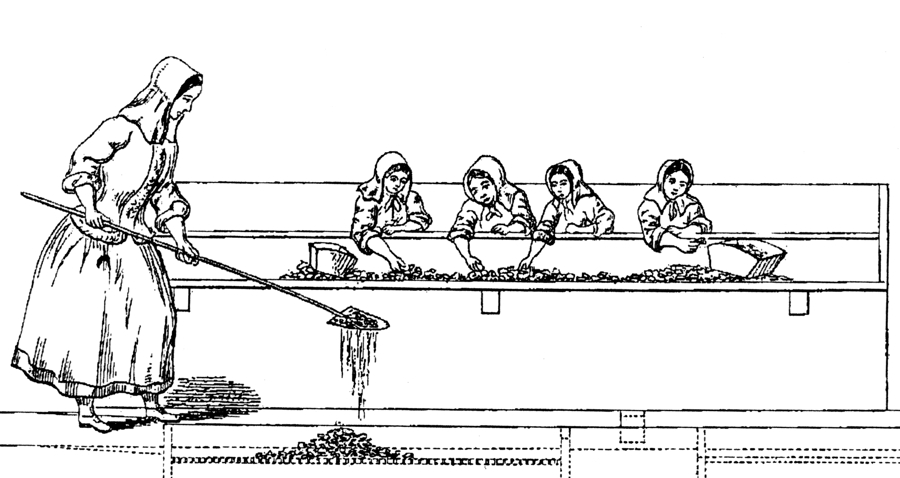

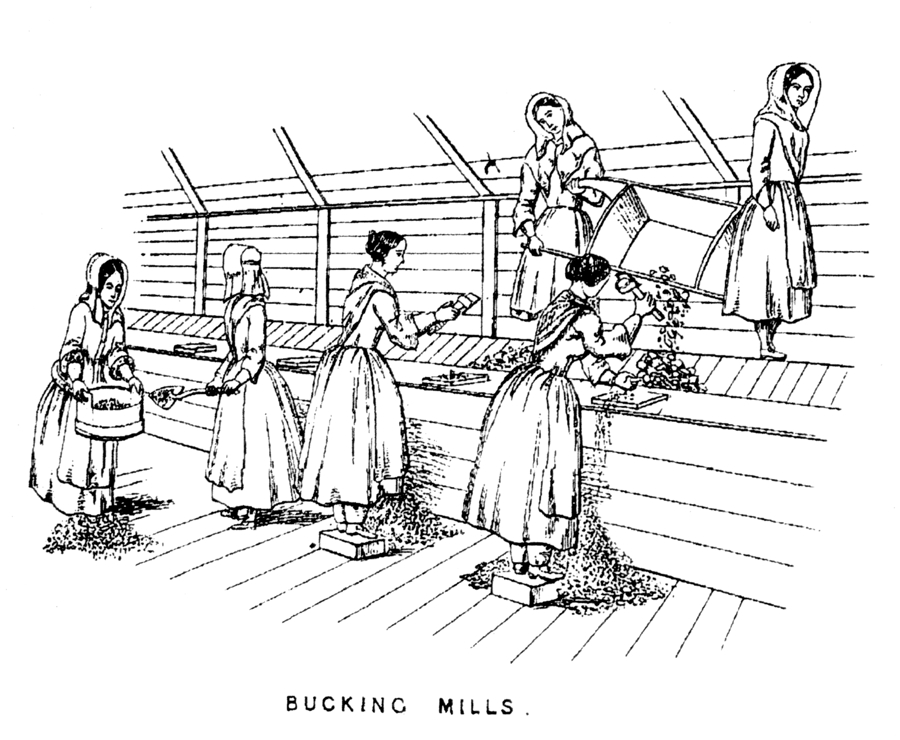

Mining was frequently a family affair. In the early 1800s, women and children were working in the mines as well. Although women are not reported as working underground, young women took work as bal maidens, dressing ore at surface. Using special hammers, they would carefully select and crush the ore to a manageable size before further processing. Heavy “bucking” and “cobbing” hammers were used for this which required particular techniques to effectively separate the ore from the waste mineral (known as gangue).

Teams of women and girls were also employed in barrowing ore around the dressing floors. They worked in pairs using hand barrows, often carrying over 68kg (more than the weight of an average man) between them. A famous bal maiden named Grace Briney was even known for carrying out “kibble landing”, a physically intensive job mainly carried out by men. Quite an eccentric character, Grace also was known to smoke a pipe and dress as a man.

Working on the mine dressing floors was hard, physical work which soon took a toll on their health and appearance. Even though they took pains to protect the faces from the sun, wearing cardboard hoods (gooks) to shade their complexions, contemporary writers noted their rough, chapped hands. Bal maidens often bought fancy gloves, which weren’t a luxury for these women, but a way of trying to stay young and attractive.

By eight or nine, a miner’s son or daughter was old enough to make their contribution to the family's income. Many boys also worked alongside the men, women and girls at surface, in the dressing of ore and in tending mine horses and machinery. This was seen as an apprenticeship of sorts before going underground when older.

Boss ladies

The majority of the managerial positions at mines in Cornwall and west Devon were occupied by men but very occasionally women appear in the mining records. Lydia Taylor is a notable example and is understood to have acted as mine manager at Wheal Lovell, Wendron, in the early 1840s. While little else is known of Lydia’s life she is also understood to have been associated with South Wheal Towan Mine, alternatively known as Wheal Lydia.

In the home

Mining was a dangerous job, and this often meant a high number of widows both young and old. Census records show that when a sister, sister-in-law, auntie, mother or grandmother became widowed, she would often move in with extended family. Records from the time also show that miner’s wives did not only work as Bal maidens, but also as farm workers on the smallholdings kept by miners to supplement their income.

This meant alongside their responsibilities in the household taking care of children, extended family and husbands, making sure were well presented and well fed, and living in a tidy if small home, these women were also tending the family’s smallholding.

Women in religion

Fairly unusually for the time women played an active part in religion in Cornwall. Methodism, the “miners’ religion”, would often have women holding “cottage religion”; informal worship in the home in 1780s to the 1830s and allowed women to actively aid the spread of the Methodist message at grass roots level. Over 56 per cent of the West Cornwall circuit (groups of congregations) were women in 1767, showing the significance of their early involvement in its spread in Cornish communities.

Methodism also encouraged pride and thrift, meaning that a miner’s home was usually clean, his children as well fed as possible and their clothes, although old, laundered and neatly patched. This took place alongside working in the mines and community commitments within religion and unpaid care work of the extended family. Women worked hard to maintain the household and their families well-fed, all on a small budget.